Almost all public spaces are filled with pictures of humans. A closer look will reveal that most of those images are lying about something: lying about delicious snacks, idyllic lifestyle, and the sincerity of politicians determined to help us… Moreover, the better their lies, the more we are drawn to look at them. Like most people in modern society, we realize that image is just a vague reflection of reality seen from a certain point of view, but we still need those pictures, and we tend to take these visual lies for granted. Pictures are paradoxical – even though we know we are being deceived, they still try to trick us.

The project “Picture Demand” consists of four works: “The Case of K. Donelaitis”, “The Case of M.K. Oginskis”, “The Case of IN” and “The Case of Homo Catinus”. These works are the result of a research on how fleeting mental images turn into materially existing images that have an effect on the world, as well as by analysing how we create portraits of people who cannot be seen or photographed. The research focused on the portraits that both continue and question the tradition of Western European portraiture. They are all unified by their quest for ‘realness’ which, in my view, is based on the opposition between objectivity and subjectivity. The aim of this research was to analyse experimentally how a subjective image functions within the domains of objectivity and science.

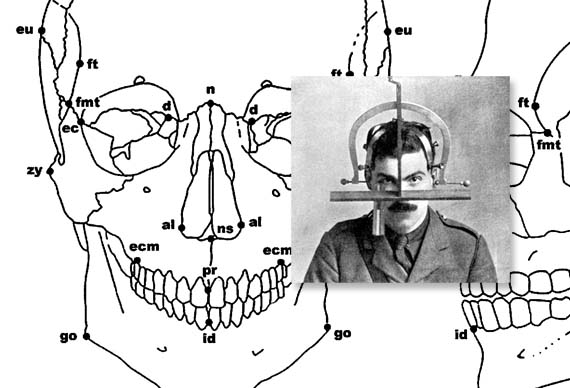

In modern society scientific data is usually held to be an objective truth. The science of craniometry provides us with the methods of measuring human skull—methods which, in a not too distant past, were used in order to determine mental capacities of humans. Today such an application is regarded as pseudo-scientific, and craniometry now has other usages. While creating a human portrait, it is very important to determine the shape of the skull, therefore the set of measurements of various skulls became central for this project. These measurements function as a basis for an objective or, rather, pseudo-objective portraiture which creates an illusion of realness. In a similar way, Catholic Church used holy relics (e.g. bones or pieces of clothing) – by incorporating them into the portraits of the saints, the Church aimed to make these images more ‘believable’.

Illustration: The scheme of craniometric points used for scientific portraits; and a craniometer constructed in 1913 by major A. J. N. Tremearne and used for taking skull measurements.

Today, the quest for objectivity seems rather comical. Either consciously or unconsciously, any kind of creation will always bear the traces of subjectivity. In the project ‘Picture Demand’ I affirm that such subjectivisation is inevitable and hold it into be the central concern in my work. I paint my subjects by looking not only at them, but at myself as well, which means that I fuse the information obtained scientifically (through craniometric measurements) with the information about my own subjective image.

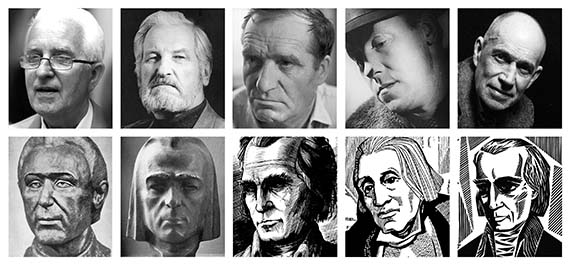

Illustration Bottom: portraits of the Lithuanian poet Kristijonas Donelaitis (1714-1780), no trustworthy portraits of whom remained; top: their authors. The first two portraits were created by using M. M. Gerasimov’s scientific method of facial reconstruction from the skull, while other three portraits were the results of artistic imagination.

Kristijonas Donelaitis (1714–1780) was a Lithuanian poet who left no trustworthy documental portraits of himself. How should he be portrayed? This case became the starting point for the ‘Picture Demand’ project.

The cult of personality sometimes manifests through the desire to acquire the likeness of an adorned leader. According to the classical scientists, things like body language, dressing style, facial expression and the shape of the skull were all traits of personality. By copying Oginskis’ craniometric points from one of his portraits, I tried to become a diplomat, politician, an uprising leader, and a composer.

"IN" —these are the two letters that separate the name of Žygimantas Augustas (1520–1572), the Great Duke of Lithuania and the King of Poland, from my own name. This grammatical difference becomes a pretext for an impersonation.

In order to find the limits of the lie generated by images, I explored the possibilities of incorporating a kettle into a human portrait. I created a system of kettle-craniometry which allowed me to paint Homo Catinus (the kettle human) in accordance with the Western European traditions of portraiture.